The Belgian priest and physicist, Monsignor Georges Lemaître died in 1966 after receiving news that his theory of the birth of the universe—what he called the “hypothesis of the primeval atom”—had been confirmed by the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation. Albert Einstein was slow in coming around to Lemaître’s hypothesis of an expanding universe, now popularly called the “Big Bang”—a term that was first meant in subtle mockery, but then he commended it to further research. Just weeks ago, scientists published evidence of the almost instantaneous expansion of all matter from an infinitesimal particle. The scale and volume of this stuns the human mind, but at least if the mind cannot grasp this, it can acknowledge it, along with the fact that there was no time or space before that “moment.” It fits well with the record in Genesis of the voice of the eternal and unlimited God uttering light and all consequent creatures into existence.

Here one must be careful in attributing to physical science an explanation of the “why” as well as the “how” of creation, and theology—equally the highest science—must not confuse itself with physics. In the sixteenth century, Cardinal Baronius said, “The Bible was written to show us how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go.” In a moment of unguarded enthusiasm in 1951, Pope Pius XII said that Lemaître’s theory proved the existence of God. He humbly backed off when Lemaître told him that a physical hypothesis could do no such thing.

No human hypothesis can tell us what God alone can reveal: that he made the world and all that is in it for his delight. When we delight God by doing his will, his delight infuses his sentient creatures with joy. The composer Gustav Holst may have employed some fanciful theology (theosophy) in giving personalities to seven planets in his famous symphony, but the ”jollity” of Jupiter is a compelling metaphor for the joy of the saints.

Laetare Sunday in the middle of Lent is not so much an interruption of the penitential season as it is an encouragement not to lose the focus of Lent and life itself on the joy that God offers us in Heaven, where there is no time or space, as it was before the world began. The Church goes “up” to Jerusalem in an earthly sense as a metaphor for moving toward the Heavenly Jerusalem which “has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God gives it light, and its lamp is the Lamb” (Revelation 21:23). This is a wonder more daunting and challenging than the most abstruse hypotheses of the most brilliant physical scientists. It moves beyond the pleasure of speculation into the purest happiness of encounter. “Rejoice, O Jerusalem; and come together all you that love her.”

by Father George Rutler, Pastor of the Church of St. Michael in New York City

Father Rutler's Sunday sermons can be downloaded in mp3 format on St. Michael's website.

Sunday, March 30, 2014

Thursday, March 13, 2014

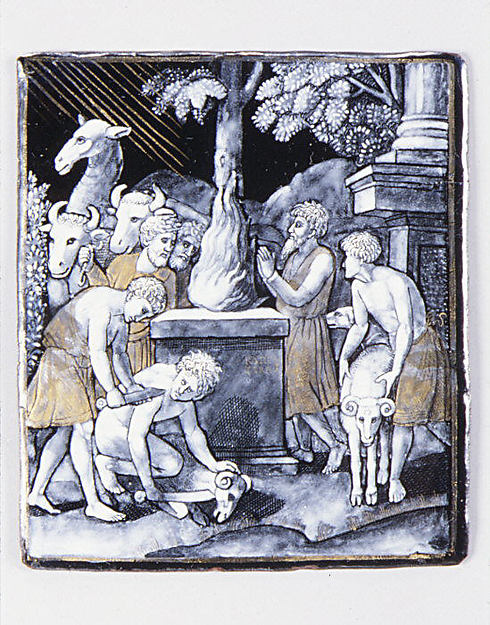

ESAU: Sin

The subject of which I want to treat next is sin, the great evil of our race, and repentance, its only

remedy. And I will take as my starting-point Esau, the grandson of Abraham, the elder son of

Isaac. You will remember that St. Paul, in his epistle to the Romans, treats Esau and Jacob as

typical, respectively, of nature and grace. Esau is the elder son by birth, but it is his younger

brother, Jacob, who is to be the inheritor of the promises. And St. Paul, anxious to maintain the

principle that God’s election is free, that it is antecedent to all merit or demerit on our part, points

out that in this case Jacob was preferred to Esau in a prophecy made before either of the two

children was born, when they had done neither good nor evil. That is t rue, and a valuable lesson.

But it is no less true that where God rejects, the ground of his rejection is to be sought, not in any

want of love on his part, but in some shortcoming on the part of the soul that is rejected. Let us

try, then, to trace Esau’s character and career – very little is told us about either – and take

warning for our own lives from the hints they give us.

ABRAHAM: A Meditation For Religious

priestly life that we must needs consider the conduct of our lives and the eternal salvation of our

souls in relation to it and in conformity with it. I might derive a lesson on the subject from almost

any part of the Bible, whether in the Old or in the New Testament. But it seems convenient for

my purpose to keep to the order of historical narration, and discuss the virtue of obedience under

the figure of the patriarch Abraham. From the very moment when he appears on the stage of

history, Abraham meets us as a man with a vocation. Almost as soon as his name has been

mentioned, we read: “Meanwhile, the Lord said to Abraham, Leave thy country behind thee, thy

kinsfolk, and thy father’s home, and come away into a land I will shew thee. Then I will make a

great people of thee.” God has a use for him, and a promise to make to him; but all that is

conditional upon a blind act of obedience; which involves saying goodbye to all the surroundings

and associations which have bounded his life hitherto. And his life henceforward is that of a

wanderer. “And he to whom the name of Abraham was given, shewed faith when he left his

home, obediently, for the country which was to be his inheritance; left it without knowing where

his journey would take him. Faith taught him to live as a stranger in the land he had been

promised for his own, encamping there with Isaac and Jacob, heirs with him of a common hope.”

Dwelling in tents; here today, he has packed up and gone elsewhere tomorrow; he has no ties to

bind him; he moves, at every turn, in obedience to a command from the divine will.

Sunday, March 9, 2014

FIRST SUNDAY IN LENT: the desert

Content if thou be to live with the Most High for thy defence,

under his Almighty shadow nestling still,

him thy refuge, him thy stronghold thou mayst call,

thy own God, in whom is all thy trust” (Psalm 90:1-2).

CONTINUE READING this meditation on the Vultus Christi blog.

And here is the complete text of Psalm 90, translated by Ronald Knox:

Content if thou be to live with the most High for thy defence, under his Almighty shadow abiding still, him thy refuge, him thy stronghold thou mayst call, thy own God, in whom is all thy trust. He it is will rescue thee from every treacherous lure, every destroying plague. His wings for refuge, nestle thou shalt under his care, his faithfulness thy watch and ward. Nothing shalt thou have to fear from nightly terrors, from the arrow that flies by daylight, from pestilence that walks to and fro in the darkness, from the death that wastes under the noon. Though a thousand fall at thy side, ten thousand at thy right hand, it shall never come next or near thee; rather, thy eyes shall look about thee, and see the reward of sinners.

He, the Lord, is thy refuge; thou hast found a stronghold in the most High. There is no harm that can befall thee, no plague that shall come near thy dwelling. He has given charge to his angels concerning thee, to watch over thee wheresoever thou goest; they will hold thee up with their hands lest thou should chance to trip on a stone. Thou shalt tread safely on asp and adder, crush lion and serpent under thy feet.

He, the Lord, is thy refuge; thou hast found a stronghold in the most High. There is no harm that can befall thee, no plague that shall come near thy dwelling. He has given charge to his angels concerning thee, to watch over thee wheresoever thou goest; they will hold thee up with their hands lest thou should chance to trip on a stone. Thou shalt tread safely on asp and adder, crush lion and serpent under thy feet.

He trust in me, mine it is to rescue him; he acknowledges my name, from me he shall have protection; when he calls me, I will listen, in affliction I am at his side, to bring him safety and honour. Length of days he shall have to content him, and find in me deliverance.

And here is the complete text of Psalm 90, translated by Ronald Knox:

Content if thou be to live with the most High for thy defence, under his Almighty shadow abiding still, him thy refuge, him thy stronghold thou mayst call, thy own God, in whom is all thy trust. He it is will rescue thee from every treacherous lure, every destroying plague. His wings for refuge, nestle thou shalt under his care, his faithfulness thy watch and ward. Nothing shalt thou have to fear from nightly terrors, from the arrow that flies by daylight, from pestilence that walks to and fro in the darkness, from the death that wastes under the noon. Though a thousand fall at thy side, ten thousand at thy right hand, it shall never come next or near thee; rather, thy eyes shall look about thee, and see the reward of sinners.

He, the Lord, is thy refuge; thou hast found a stronghold in the most High. There is no harm that can befall thee, no plague that shall come near thy dwelling. He has given charge to his angels concerning thee, to watch over thee wheresoever thou goest; they will hold thee up with their hands lest thou should chance to trip on a stone. Thou shalt tread safely on asp and adder, crush lion and serpent under thy feet.

He, the Lord, is thy refuge; thou hast found a stronghold in the most High. There is no harm that can befall thee, no plague that shall come near thy dwelling. He has given charge to his angels concerning thee, to watch over thee wheresoever thou goest; they will hold thee up with their hands lest thou should chance to trip on a stone. Thou shalt tread safely on asp and adder, crush lion and serpent under thy feet.He trust in me, mine it is to rescue him; he acknowledges my name, from me he shall have protection; when he calls me, I will listen, in affliction I am at his side, to bring him safety and honour. Length of days he shall have to content him, and find in me deliverance.

Friday, March 7, 2014

THE FLOOD

I hope to continue to post chapters from Ronald Knox's 'A Retreat For Priests' during Lent. The previous post - Creation - was Chapter 1. Here is Chapter 2, The Flood:

I have spoken of man’s creation and his fall; it is natural to pass on from that to an incident

which follows at a very short interval in the sacred writings, the Flood. It has been pointed out

that almost every people retains the memory, or has preserved the legend, of a great deluge at

some remote period, which made a clean sweep of living creation and involved, as it were, a

fresh start. Whatever else the Flood was or did, it seems quite certain that the memory of it is

branded on our race-consciousness; the details of it may be dimly remembered, like a child’s

nightmare, but the tradition is there – that the world God had made needed to be remade, for all

practical purposes, after being buried under a flood.

What is the lesson which this tradition teaches us? Why, first and foremost the lesson of our

conservation. We might have been tempted to suppose, indeed, people often have supposed, that

God simply created the world and then lost interest in it; left it to go its own way, according to

some automatic principle of control which he had devised for it, without interfering in its

destinies further, or busying himself about its welfare. Well, we all know that such a conception

is wholly unsatisfactory as a matter of philosophy; that it is not enough for God to have created

us; he must needs hold us in being by a continuous exercise of his power, lest we should slip

back into the nothingness from which we came.

CONTINUE READING

Sunday, March 2, 2014

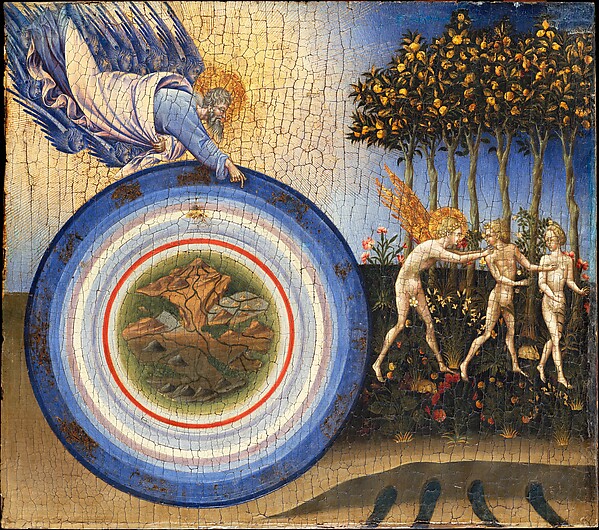

CREATION: Remember, man, that thou art dust ...

[... in this meditation I am using as my starting-point the Creation of Man, and the incident

which follows on it with such pitiable rapidity, the Fall of Man. I would just remind you of the

verse in which Adam’s creation is described: “The Lord God formed man out of the slime of the

earth, and breathed into his face the breath of life, and man became a living soul”. Let us look,

first of all, at that side of the picture which humiliates us, which puts us in our place. The Lord

God formed man out of the slime of the earth – I don’t think that means we are necessarily

bound to regard the human race, so far as its bodily composition is concerned, as a special

creation; after all, it does not appear to have been a creation ex nihilo. And certainly we are not

meant to draw any conclusions about the exact chemical composition of the flesh we wear. What

this verse does emphasize is the fact that man, on the one side of his nature, is a material being;

is akin, not merely to beasts and birds, but to the lifeless clay under his feet. We are matter, we

are potentiality; we change, as the years go past, every particle of the material tissue in our

bodies; and when we die, we rot in the ground.

So it does not worry us, when angry materialists tell us that we all came from a monkey;

“Monkey?” we say; “why, I was made out of the slime of the earth.” And, for fear we should be

in danger of forgetting our origin, the priest who celebrates the community Mass on Ash

Wednesday is directed to say to us on that occasion, Memento, homo, quia pulvis es, et in

pulverem reverteris. Pulvis es, we are slime of the earth, clay of God’s fashioning; we did not

make ourselves, he made us; his rights over us are absolute, to make, to break, to remake. Pulvis

es, we are not like the angels, who, though created beings, are yet creatures of unalloyed and

unconfined spirit; we have gross animal bodies, with gross animal needs. Et in pulverem

reverteris, the day will come when this body of ours, so delicately fashioned, so exquisitely

proportioned, will decay like dead leaves or fungus, and pass into the general stock-pot of inert matter. Et in pulverem reverteris, the proudest of our civilizations may be buried, years hence,

like Babylon or Carthage, beneath the drifting sand. No echo of vanity in our hearts but may be

silenced by that terrible formula, Pulvis es, et in pulverem reverteris.

from 'A Retreat For Priests', by Ronald Knox

READ the entire chapter in PDF.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)